DNA from 25,000-year-old tooth pendant reveals woman who wore it

A new technique for extracting DNA from ancient artefacts without destroying them could give us unprecedented insights about the people who made or wore them

By Christa Lesté-Lasserre

3 May 2023

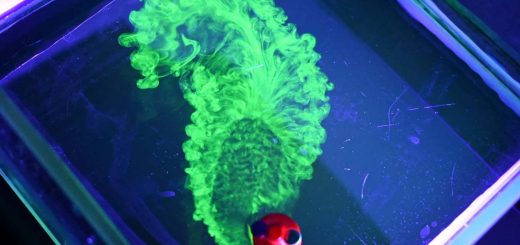

A pierced deer tooth discovered in Denisova cave in Siberia

Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology

DNA that seeped into an elk tooth pendant about 25,000 years ago has yielded clues about the ancient woman who wore it.

The tooth, worn as a necklace bead, probably absorbed DNA from the person’s sweat as it lay against her chest and neck. Marie Soressi at Leiden University in the Netherlands and her colleagues were able to extract that DNA without damaging the tooth through a new process that took eight years to develop. The technique might reveal unprecedented details about the social customs and gender roles of ancient populations, says Soressi.

“For the first time, we can link an object to individuals,” she says. “So, for example, were bone needles made and used by only women, or also men? Were those bone-tipped spears made and used only by men, or also by women? With this new technique, we can finally start talking about that and investigating the roles of individuals according to their biological sex or their genetic identity and family relationships.”

Advertisement

Scientists have often suspected that ancient tools, weapons, ornamental beads and other crafted artefacts contain DNA from the people who touched them. But getting DNA out of these objects typically means removing sections for analysis – causing permanent damage. “We absolutely didn’t want to do that,” says Soressi.

To see if DNA could be coaxed out of ancient artefacts without destroying them, Soressi and her colleagues tested numerous combinations of chemicals and heating regimes on 10 previously excavated artefacts from Palaeolithic caves in France. They found that placing them in a sodium phosphate solution and raising the temperature incrementally from 21°C to 90°C (70°F to 194°F) led to the release of relatively large amounts of human DNA with no damage to the specimens.

The team then tested the procedure on another 15 excavated bone specimens from one of the caves. Genetic sequencing revealed DNA from many different humans – probably the scientists and technicians who had worked with the artefacts across the years, says Soressi.